On April 7, news outlets reported mounting evidence that tiny subatomic particles called muons seem to be disobeying the known laws of physics. Muons are akin to electrons but heavier and radioactive and, well, wobbly. When shot through a magnetic field at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) in Batavia, Illinois, the muons did not behave as had been predicted. The muon’s aberrant behavior poses a firm challenge to the Standard Model, the collection of equations that scientists use to explain how subatomic particles interact. The researchers at Fermilab now believe there must be something there in the dark—a different particle or a fault in the Standard Model itself—that is contributing to the deviation. “What monsters might be lurking there?” asked Dr. Chris Polly, a physicist working on the experiment.

Two Categories of Laws

The scientists of Fermilab aren’t the first to call into question the permanency of those observed patterns we refer to as the laws of nature. In the fourth chapter of his book Orthodoxy, G. K. Chesterton writes about how in the physical sciences, we often call things laws (the law of inertia, the law gravity, or the Standard Model laws of quantum mechanics), but in reality, these are only weird repetitions that depend in large part on circumstance and environment. Gravity seems to work differently in open space than it does on the surface of a planet, and it definitely works differently at the subatomic level.

Different from the laws of nature are the laws of logic, that is, “the science of mental relations, in which there really are laws.” Even in the old fairytales—where the laws of nature are transcended the moment a fairy godmother whispers “bippity boppity boo”—logic still applies. If Cinderella is younger than her stepsisters, then those stepsisters must be older than Cinderella; it cannot be otherwise.

Two Diametrically Opposed World views

The laws of logic, Chesterton believes, are true because they speak to the very nature of things. Laws of nature, however, only describe observable effects. Although we may be able to explain something of how gravity or entropy work as patterns, the deeper we dig below the surface—as Fermilab’s latest experiments demonstrate—the less we can articulate why they work the way they do. Chesterton put it this way:

We cannot say why an egg can turn into a chicken any more than we can say why a bear could turn into a fairy prince. As ideas, the egg and the chicken are further off from each other than the bear and the prince; for no egg in itself suggests a chicken, whereas some princes do suggest bears . . . When we are asked why eggs turn to birds or fruits fall in autumn, we must answer exactly as the fairy godmother would answer if Cinderella asked her why mice turned to horses or her clothes fell from her at twelve o’clock. We must answer that it is magic.[1]

Here Chesterton gives us the difference between a naturalist—or materialist—and a supernaturalist view of the world.

A naturalist believes that the order and affairs of existence are all there is. So, when new evidence calls into question the Standard Model as we thought we knew it, the simple fact that there’s a deviation makes the papers. The anomaly opens the door to a great unknown and the materialist responds with a bit of fear: What monsters might be lurking there in the shadows?

A Christian, on the other hand, believes that God intervenes in the order and affairs of existence. So, a believer is less worried when expectations, the laws of science, and the world itself is bent. Even if monsters are hiding in the corners of our reality, the Christian’s faith can stand.

Better Stories for the Next Generation

You see, God has given Christians a set of biblical stories that can help to settle our hearts even when the things we depend on most in this world seem shaky. He’s given us the miracle stories in the Gospels, accounts about times when Christ’s touch and wonder-working words contravened natural order of things in order to show us his power and plan.

To understand the importance of miracle stories, it can be helpful to think about how they compare and contrast the fairy tales that even unbelievers tell their children in our culture.

Fairy tales point toward big truths about reality that are normally hidden from our sight.

In Orthodoxy, Chesterton wrote about how Jack the Giant Killer teaches a lesson about “manly mutiny against pride.” In Beauty and the Beast, he saw the truth that “a thing must be loved before it is lovable.” For the old philosopher, Sleeping Beauty functioned as an allegory. It tells “how the human creature was blessed with all birthday gifts, yet cursed with death; and how death also may perhaps be softened to a sleep.” In each of these tales, he saw larger truths—laws more enduring than the laws of nature—truths that are taught through the magic.

In another essay, Chesterton wrote about how fairy tales don’t tell children that evil exists; children already know that monsters and dragons and bogeys—to use Chesterton’s term—exist. Instead, “what the fairy tale provides for [the child] is a St. George to kill the dragon.”

I’ll never forget hearing fantasy author Andrew Peterson talk about how we don’t use our imaginations in the ways that we did when we were kids. “We may daydream about a new job, a new iPhone, or a new home,” he said, “but we certainly don’t spend our time thinking about dragons, fairies, swords, and giants.” As we grow up, we start to forget what it’s like to use our imaginations for good both because we think we’ve got the world figured out and because we begin to lose the sense of wonder that captured us as children. The older we get the more our eyes are drawn only to what’s in front of us, and we fail to remember there is an entire world beyond what our eyes can see! Fairy tale darkness experienced through great stories is meant to shed light on life as it really is in the present—life in a fallen world, which is presently ruled by evil principalities and powers, with whom we are at war.

But at best, fairy tales are only shadows. With the miracle stories in the Scriptures, children discover what it means to encounter Christ himself.

The miracle stories pull back the curtain and reveal the Savior to whom Jack and St. George and Prince Charming dimly point. You see, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John didn’t just record particular supernatural wonders that Jesus performed. Each of these wonders also serves as a theological proclamation. They tell us who the Savior is, and they invite us to encounter him.

When we read the story of water turned into wine, we meet the one who is making all things new. When we hear of empty nets filled to overflowing, a demand is placed upon own lives to become fishers of men. When he touches Bartimaeus’s eyes, our own eyes are opened. And when his word calms the sea, our fears are stilled.

We rehearse these stories and tell them to children, because the miracles declare in no uncertain terms that the Savior has come as their righteousness, substitute, and victory. When we talk about Christ healing the sick, delivering the demonized, and raising the dead, we also announce the good news that Satan, sin, and death are in retreat. When we hear “rise up and walk,” we—adults and children alike—can stand up in our hearts and believe.

There’s a Big Difference

You see, the decided difference between fairy tales and the miracle stories in the Gospels is that the Bible’s stories are true. These historical stories from Jesus’s life not only reveal the true nature, but in their telling, the living Christ himself is present. And in a broken world where entropy, failed science, and monsters reign, we desperately need his presence and healing touch.

We need the stories of Jesus’s miracles because in the face of the great fears both kids and adults face in our world, these accounts remind us that there is a good and powerful Creator at work as well. The Christian worldview we learn from the Gospel accounts helps us to take comfort when we’re looking into the cozy microscopic corners of God’s little universe. With the miracles as our frame of reference, we won’t be surprised when what we find in those crannies is not a magical monster nor mindless matter obeying impersonal laws but the God of mystery behind the muons holding the world together by the word of his power (Hebrews 1:3).

[1] G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 57.

Photo by Kevin Fitzgerald on Unsplash.

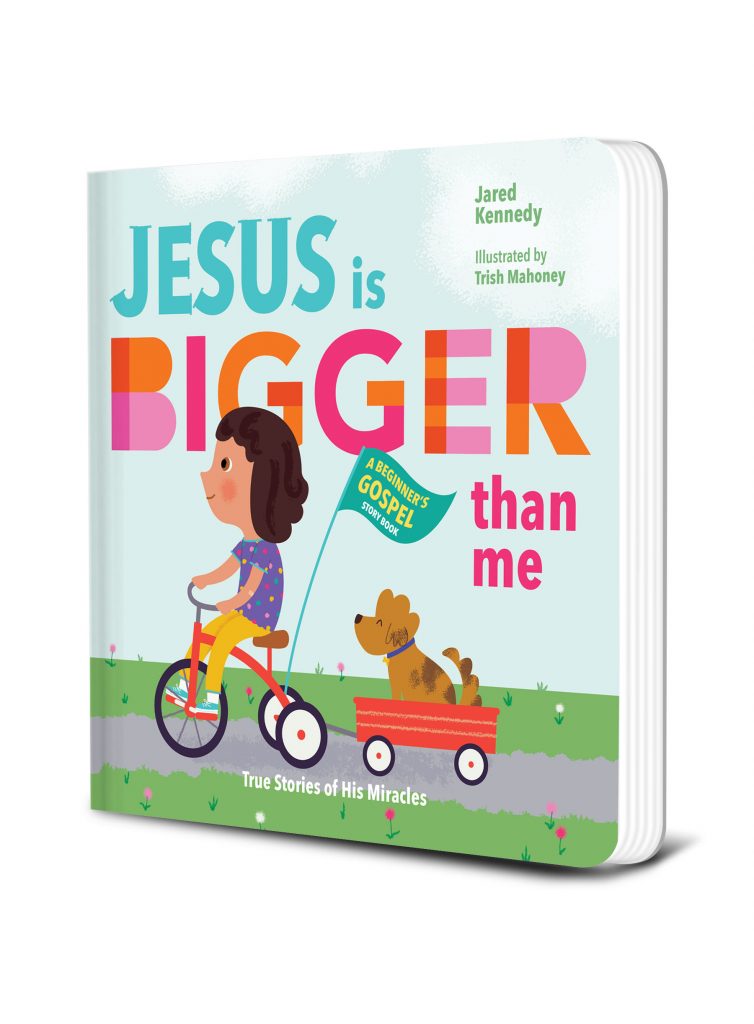

Jesus Is Bigger Than Me: True Stories of His Miracles

Jesus is bigger and more powerful than any superhero. He can turn water into wine, calm a stormy sea, give sight to the blind, and even raise the dead. When Jesus is with us, God is with us. Children will learn that Jesus is God through the story of his miracles and be encouraged to go to him for help because he cares for them.